I hope that this web page can become a collection of information and a resource for family and friends. I plan to update, and/or, correct this page as new information is discovered.

Thanks for your help.

Eugene (Gene) D. Johnson (son of Ellsworth and Rowena Heffley, grandson of Iver and Anna Ryan and great grandson of Sevn and Sigri Berg - JOHNSON)Johannes Mikkelsen Haugen (1806 – 1872) born at Onstadeie, Aurdal, Valdres, Norway.

446 Trinity Drive, Allen, TX 75002

469-675-1316

Last updated: August 4, 2004

his father: Mikkel Johannesen Haugen , son of: Johannes Einerson Aaberg (1708 - 1792) and Giertrud Mikkelsdatter Koldsbreche

his mother: Agathe Olsdatter MidtStrandeie (1776 - 1828) daughter: of Ole Arneson Midtstrand (cr.1729 - 1791) and Ragnild Helgesdatter Midtstrand

Johannes married in 1831: Marit Svendsdatter Gausdgereir (1807 – 1898)

her father: Sven Thordson Gausdgereir (1778 - 1837) son of: Thord Thoreson Gausaker (1746 - ?) and Marit Svendsdatter Ulneseie

(1747 cr. 1811)

her mother: Sigri Amundsdatter Lien (1763 - 1841) daughter of: Amund Svendsen Lien (cr. 1721 - 1805) and Berte Olsdatter Lundane

(cr. 1729 - 1797)

(Marit immigrated to Stanton County, Nebraska, in 1873, after her husband died, along with her son Ole and daughter Ragnild. She is burried in the Stanton County, Nebraska, "Norwegian Cemetery".)

Johannes and Marit had the following children:

1. Agathe Johannesdatter (1830 – between 1861 & 1865), Agathe did not emigrate

2. Johannes (John) Johannesen (1834 – 1884), John emigrated in 1866 with wife Margit Hallsteinsdatter

3. Svend Johannesen (1837 – 1931), Sven emigrated in 1868 with wife Sigri Iversdatter Odegaard

4. Siri (Sarah) Johannesdatter (1844 – 1919), Sarah emigrated in 1868 with husband Halver Halverson

5. Berit Johannesdatter Haugen (1846 – 1909), Berit did not emigrate

6. Ragnild Johannesdatter (1848 - 1943), Ragnild emigrated in 1873

7. Ole Johannesen (1852 – 1937), Ole emigrated in 1873

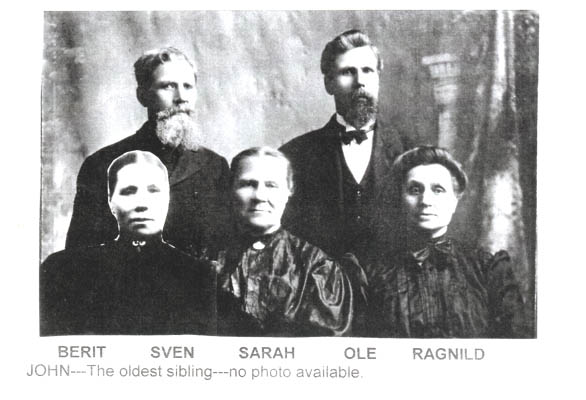

The picture below shows Sven and some of his siblings:

This page will describe the Elkhorn Valley around the time John and Sven Johnson arrived.

The following is from the Stanton Register dated Thursday, April 15, 1976 page 9:

“District 19 to note 100th.

By Margaret Mastnt

Remember when some of the boys set fire to the toilet and Mike Melcher was in it? (Locked in of course) Mike also recalls a flood, his dad brought him to school in a wagon. The water was 2 feet deep all around the school house. They had to lay planks to the cob house to go to the toilet. Enough toilet stories! Mike remembers doing embroidery work in the 6th grade as a reward for getting his school work done. (Wish we could see that dresser scarf he made!).

Does anyone recall way back in 1908 and 1909 when Henry Shultz made a Buckskin pony out to the country to teach rural school? Henry, a retired mortician is the oldest living former teacher and still lives at Stanton.

What about the controversy between the “Mudhens and Sandhillers” and how one night the old school house got moved! That was the beginning of the new school house.

It really happened in rural District 19. These and many more stories will be retold at the 100trh Anniversary celebration of District 19, which will be held Sunday, May 16 from 12 PM to 5 PM at the school house…

The original frame school house, 18 x 28 was 10 feet high with brick basement, 6 windows and two doors and was built in April 1876. Ole Loe was the first teacher. He taught 4 months, starting in November for $25 per month. The new school house was built in 1916…

The picture below was taken in 1923 of District 19 students:

Kneeling (from left to right): Dallas Timperley, Emil Mastny, Martin Voelker, Eugene Everson, Richard Voelker Janes Bearden.

Second row: Goldie Timperley, Maxine Everson, Bernice Melcher Bussman, Phyllis Ackerman Johnson, Ella Voelker Houfek, Ethel Everson, Nettie Bearden

Back row: Lloyd Timperley, Clifford Johnson, Francis Dickinson, George Voelker, Ellsworth Johnson, Harley Melcher

The article copied below, describes a conflict between the local Indians that occurred in 1848, just 20 years before the brothers arrived.

STANTON SCENE OF BLOODY INDIAN BATTLE

Sioux-Omaha Battle Related in interesting Detail Read by – Mrs. Ed Hushaw

The following undated article was written by Mrs. Gertrude Miller Namur.

Along the banks of the beautiful Elkhorn, in that part of Nebraska now known as Stanton County and on the site where the thriving little city of Stanton stands, was fought many years ago, one of the fiercest battles between the red men that ever took place in the whole west, and after the engagement was concluded hundreds of Indians, Sioux, Poncas, and Omahas—both sexes, and little papooses, lay scattered over miles and miles of hill and valley, while the grass-scented air was laden with moans and wailings for lost braves and their families.

The true history, so far as known, of this battle has never been written and today it is impossible to obtain exact data. Indian tradition being depended upon—that and brief memoranda left by the late Cr. W.L. Bowman of Stanton County, who was the accredited historian of western Nebraska, and had many talks with Indians who participated in the slaughter. The doctor fixed the date of this battle as the summer of 1848, when the summer hunt was in full force.

BONES FIX BATTLE SITE

As to the location of the battle, there is no question, the bones of dead Indians, already unearthed by the hundreds, bearing testimony.

As related to Dr, Bowman, by old warriors who participated, the real fight opened in the valley just south of Stanton. The Omahas and Poncas being camped on the banks of the Elkhorn in large numbers, their camp extending south of the Elkhorn up along the Butterfly and out north along Indian creek, two streams that empty into the Elkhorn near the present town of Stanton. However, the first skirmish took place between a party of Omahas and Poncas near the present town of Norfolk, where the Sioux surprised a small hunting party and killed several of them two days prior to the beginning of the big engagement on the Elkhorn.

FOUR THOUSAND SIOUX

Just how many Indians were engaged in the fight, no one is able to accurately determine, but Indian history places the number of Sioux warriors engaged at 4,000, while there were but 1,500 Omaha and 300 Ponca warriors. There were no women with the Sioux, but the Omahas and Poncas had with them 4000 women, old men and children, making a hunting party of 6000. Thus, it will be seen that the Sioux outnumbered the Omaha party two to one as to fighting force. Again the Sioux were really on the war path while the Omahas and Poncas were on a peaceful mission, securing buffalo.

SPOTTED TAIL FOUGHT AS A BOY

In the engagement were many Indians who later became known all over the world as great fighters. Spotted Tail was a mere boy at that time, but took an active part in the fight. It is said that at the battle on the Elkhorn he laid the foundation which in later years made him one of the most powerful chieftains the Sioux ever had. It happened this way: When the fight was the fiercest, young Spotted Tail jumped on a bareback pony and rode directly in front of the Omaha and Ponca line of defense and waving his arms in the air defied anyone to shoot him. Many a brave tried to do so, but he escaped back to the Sioux lines unscratched. This act of bravery gave him a standing that in time made him the leading chief of this people.

According to Historian Bowman’s notes, which he prepared after interviewing many Indians who were in the great battle—a battle that startled the whole Indian world—the Omahas and Poncas were led to believe that after the Norfolk skirmish the Sioux had drawn off and gone their way, but this was not true. Only a very small part of the four thousand Sioux had been seen when the skirmish took place, and consequently the Omaha and Poncas had no idea that such a large party of their enemies was in the county.

BELIEVED SIOUX HAD LEFT

The second day after the Norfolk skirmish passed and all was quiet, Chief Logan of the Omahas, who was ranking chief the night before the slaughter began, called a council of leading men and they heard reports from runners who had been sent out who reported that they found no Sioux and believed they had gone north. Then it was decided that early next morning the hunters would start after a heard of buffalo that had been seen the day before south along the Butterfly, and after another day’s hunt, they would begin working their way east toward the Missouri River, not far from where Omaha now stands. The squaws had cut and dried all the meat already secured and the winter’s supply was almost complete.

CHIEF LOGAN’S MISTAKE

That night Chief Logan post sentries and the hunting camp went peacefully to sleep to dream of their home down on the “Big Muddy”.

For once Chief Logan, contrary to the rule of warfare , civilized or uncivilized, made a great mistake, one that at the battle on Logan Creek two days later cost him his life at the hands of the Sioux.

In the camp of the Omahas and Poncas was an Indian boy of the Omaha tribe who later became one of the most powerful chief’s of the Omahas, Two Crow, and it was from his lips that Historian Bowman received a detailed account of the great battle; old Two Crow relating the same story to Thomas H. Tibbles of Omaha nine years afterwards. Said Two Crow: TWO CROWS STORY

“I remember the fight well. It lasted three days and part of three nights although there was but little fighting at night. I was a mere boy but I took part and killed some Sioux the great enemies of my people. After the village had gone to sleep, I got up and walked out where the sentries were. All was still and no sound came except from coyotes and owls. Once or twice I heard a coyotes’ call that did not sound right to me but the man on watch I was with did not think anything of my suspicion. What made me more suspicious perhaps was that the cry of the coyote was answered too promptly and the calls seemed to move to regularly from the north to the south. But I was only a boy and my advice was not cared for. Had my people known that those calls came from Sioux warriors, and that they were crossing the Elkhorn below our village in large numbers, they would have been better prepared for what happened at dawn next morning, but they slept quietly as if at home.

VILLAGE DIVIDED BY RIVER

“Our Village was mostly on the north side of the Elkhorn near where the Elkhorn is now crossed by a bridge at Stanton. Part of the camp was on the south side of the Elkhorn. Some of the families were camped out as far as five miles along the Butterfly and some out along Indian Creek. We were scattered a great deal. We had feared nothing and had not been molested except when some of our hunters had been attached by the Sioux farther up north (near Norfolk). We knew the Sioux were our enemies and would kill us but we had a large party and felt secure. We had about 6,000 people in our party, there being about 1,500 Omaha men and 500 Ponca men, the rest being women , children and old men, so you see we had a big force and we were armed as well as we could be then. We had guns and bows and arrows. Our guns were muskets and long-barreled rifles. Our men could shoot straight. One of then could drive and arrow through a buffalo from a horse while going at full speed. Our head chief was Chief Logan and he was proud of his men. He was a great chief but his heart was too warm. He trusted others too much. That was his great mistake.”

ATTACKED AT DAWN

“It was late when I crept into my blanket and went to sleep. It seemed hardly a moment when I was aroused by awful yells from the south and east of out camp. We were being attacked just at daylight by the Sioux under Chief White Wolk. Chief Logan at once began to get his men in line for battle. Off on the south side of the Elkhorn a sub-chief, Lone Chief an Omaha, was also busy. The dogs barked and the ponies made a noise, for they smelled the Sioux and didn’t like them. The old men and the women and children began to move back behind the village. Chief Logan met the Sioux with guns and arrows and many Sioux were killed. I saw one Sioux fall a few feet from where I was. Chief Logan had killed him with him a hunting knife. He was a chief, but I didn’t know his name.

We were so busy defending our own part of the village that we had no time to think of our people on the south side of the Elkhorn or up along the butterfly or Indian creek. The fight at the main village lasted for two hours and then the Sioux drew off to the sand hills to the northeast. Those that were on the south side of the steam crossing to the north side. Many, many dead Omahas and Poncas lay all about, some in awful pain. We had lost many warriors and many women and children had been killed. But we had no time to lose in the mourning over our friends and relatives. We knew the battle would begin again as soon as the Sioux could reform their lines and decide on what action to take next.

In a little while, warriors came from up the butterfly and Indian creek and told that they too had lost many men, but the main fight had been down on the Elkhorn. Chief Logan sent runners to bring in all our people that were alive and decided to make a grand stand on the south side of the Elkhorn, near where Indian creek runs into the Elkhorn. The old men, women and children were placed back of the main village and our warriors lined up on the steep bluff of the Elkhorn and out north as far as where the palefaces now have a burying ground.

We waited all day and the Sioux didn’t attack us again. We hoped that they had drawn off, but we feared not. They had not gone, but were only resting and burying as many of their dead as they could get. We had lost heavily on our own ground and as we couldn’t bury our dead on a battleground we had lost, we had to leave then there for the wolves to destroy. But they were good Indians and the wolves couldn’t harm them. Their spirits had gone to the happy hunting ground and only their bodies were left. It made us very sorry that we could not carry our dead to the hill and bury them, but we couldn’t do that for the Sioux were near us. We just looked to the Great Spirit for success and prepared for another battle.

A MIDNIGHT MARCH

Night came down and the Sioux had not attacked us. Chief Logan called his head man and they talked a long time. Then at midnight the camp was quietly aroused and we started east, hoping to get away to our homes on the “Big Muddy”.

The moon came up bright and clear and the night was a beautiful one. We put the women and children in the middle and marched all night but we could make but little head way. We had much meat to carry and much camp things, we had some ponies to draw the loads of meat and some to ride but Chief Logan had the warriors ride the ponies. Just at sunrise we got down near what is now Wisner and made camp and cooked our breakfast. We were hungry and very tired, for we had marched all night and our feet were very sore.

We rested until near noon and then expected to start east to our homes. The runners had reported that the Sioux were behind us in large forces and that some of them had been seen a few miles ahead of us, but we hoped that we could fight our way through. We knew if we didn’t get away very soon we never would, for our forces had been very much weakened. We had lost 500 warriors in the battle of the Elkhorn besides many women and children and old men. Our hearts were very heavy and the old women sang songs for the dead and beat their breasts. The warriors said nothing but were ready to fight and die if they had to. It seemed that the great father had forgotten his children for we had done no harm to anyone.

I was with the first warriors that started. I had a gun that shot a long ways. It was a great gun. My father gave it to me. He had been in the white man’s war one time and had little nicks in its stock. I was told that each notch meant an enemy killed and was very proud of my gun.

SIOUX RENEW ATTACK

We had hardly started when the runners came riding in very fast and said the Sioux were coming. The warriors were massed for defense and just then we saw the Sioux coming on the run on ponies a mile away. We waited and very soon they were on us in very large numbers. Our warriors fought then from the first and many Sioux were killed, but they seemed as the blades of grass. Two sprang up where one went down. Our men fell right and left.

Chief White Wolf of the Sioux divided his forces and surrounded us. Chief Logan of our people saw a chance to break through the lines of the Sioux and gave orders to advance. We did so in regular Indian order, fighting as we went. We did break through the Sioux lines, too, and got over on the sand creek near what is now West Point, we hoped we had escaped but it was not so. We were again attacked there and lost many more men and nearly all of our supplies. Our warriors fought bravely and we beat back the Sioux. They drew off and seemed to be leaving. We didn’t wait to rest but started on east again as fast as we could go. Our ammunition had run very low and we had to depend on bows and arrows and our knives and tomahawks.

DEATH OF CHIEF LOGAN

We camped that night on Logan creek, east of what is now West Point. We slept as we could, but we feared much. We ate much that night because we didn’t know when we might eat again. Early next morning, the Sioux again attacked us and again we had to fight our way through their lines. Just as we were breaking through the lines to the east, Chief Logan was shot by a Sioux and killed. Chief Lone Foot then took charge and we continued. We lost many more of our men, and more women and children were killed. Many were left on the ground badly wounded. We carried all we could with us but there were many of them. We fought until nearly noon when the Sioux drew off and we hurried on east and escaped. They didn’t attack us again. We had killed many Sioux but they killed nearly all of our people. We got away with only about 800 warriors and we lost about 3000 men, women and children in all the fights. We were very sad. We had to stop and rest. At last we got back to the “Big Muddy” and were safe, for the Sioux didn’t dare to come here as we had many friendly Indians on the other site of the “Big Muddy”.

This ended the data a recorded by Historian Bowman, who knew Indians of the plains as few other men did, he having lived for years dating from pioneer times, where the Indians used to roam and could speak their language like a tribesman. He was a great favorite among the Indians because of his profession, having saved many a life after the medicine man had given up hope.

At Stanton lives W. G. McFarland, a county official. He went to that part of the state in 1868 and often talked with Indians who participated in the great battle of the tribesmen. His data corroborates that of the late Dr. Bowman. One day an old Indian showed Mr. McFarland a scar on him and which he said he received in the battle between the Sioux and the Omahas and Poncas. The old Indian, and Omaha, said there had never been another battle in the world like that one and he was only surprised that a single Omaha or Ponca escaped alive.

Banker Eberly, of Stanton, who has lived many years in Stanton, has also heard many times the talks of the great conflict. Neither he nor anyone can say how many Indians were killed but according to Indian tradition there must have been over three thousand men, women, and children. His version of the fight does not differ materially form that of old Two Crow who was a participant.

THE OMAHA GROUNDS

That the Omaha, who were friends of the Poncas, had a right to hunt on the territory where the Sioux attacked them, there is no doubt, according to history. As early as the first quarter of the eighteenth century, the “OO-a-has”, now known and the Omahas had their homes on the north side of the Missouri river, at and near the mouth of the Sioux river. Subsequently, they crossed over and located on the Niobrara in what is now Nebraska. Being pursued with relentless fury by the Sioux, they again moved, this time going down the Missouri river, and located north of the Platte River. Making this their permanent homes, they lay claim to all the territory north of the Platte, west of the Missouri, but not extending north of the Missouri. That is how they came to be possessors of what is now Nebraska territory when the whites came.

DEPLETED BY SMALLPOX

It might be well to state that the Omahas and Poncas had but recently passed through an awful scourge of smallpox, and that their numbers had been greatly thinned by the disease when the Sioux attacked them. Had they had their usual fighting force the battle might have gone the other way, for the Omahas and Poncas were good fighters. The Sioux knew that the smallpox had been busy and took advantage of the fact to attack when the ranks were depleted.

It was five years after the battle on the Elkhorn that the Omahas found heart to venture as far west as Stanton, which they then did in large force. Their little boys had grown to be men and were warriors. It was in the summer of 1853 that the Omahas and a few Poncas set out on the trip. They were going to try and find the bones of their dead and bury them. Five long years had left nothing but bones scattered by wild animals far and near about the scene of the different battles. But there were thousands of bones found—a skeleton here and a skeleton there still intact. Scattered also, over the battle ground lay the bones of many Sioux, the Sioux having not returned to bury their dead when they retreated to their northern home.

It was no trouble to tell a Sioux skull from that of Omaha or Ponca, the heads being shaped differently. There is also a difference in the shape of the thigh bone the Indians claimed, which enabled them to pick out their own people. Some of the smaller bones were so much alike, if not exactly alike that they could not be separated if the skeleton had been torn apart. But the Omahas and Poncas did the best they could working for days and days under a boiling mid-summer sun on their mournful mission.

INDIAN BURIAL GROUNDS

After all the bones that could be found had been gathered and laid in a pile, the Indians dug a great grave on the top of a high hill just north and east of the present site of Stanton, and buried them with Indian ceremonies. After the big grave had been filled, the old bones of a great many more Indians were found at the former camp up on the Butterfly and Indian Creek and they too were carefully gathered and separated for burial. It was not wise, the Indians said, and would displease the Great Spirit, to reopen the big grave so the rest of the bones were buried in individual graves for the most part at various places on the hill not far from the big grave. Some of them were taken west to the present site of Stanton and buried on the hill there. The Sioux ones were not buried except as they became mixed with the Omahas and Poncas as doubtless they often did.

Having performed the last possible service for the departed braves and others, the Indians departed for their homes down on the Missouri.

Time passed on, but the defeated Indians had not forgotten. White settlers had come and the prairies of the west were dotted with farms.

FINDS BONE OF SIOUX VICTIM

Into that part of the state had moved Thomas H. Tibbles, the well known newspaper writer. He was well acquainted with old Chief Two Crow, the Omaha. Once old Two Crow visited him and one morning absented himself without explaining where he was going. Mr. Tibbles then lived several miles from where the Omahas and Poncas had made their last stand and where they escaped from the Sioux. At night, old two crow returned and walking up to Mrs. Tibbles held forth a bone. She inquired what it was. The old chief said: “that is the thigh bone of a Sioux I killed when we had our last fight with them. I had my gun and two boys were with me. We stayed back to help watch for the Sioux to follow. We saw three Sioux through the bushes. I took good aim and killed one of them. The others ran away. That was the end of the fight and I killed the last Sioux. The bone of an enemy is good luck if you touch it. The Sioux was an enemy.

TWO CROW WAS SURPRISED

Mrs. Tibbles, when she ascertained what the bone was, refused to touch it which greatly surprised old Two Crow. When he went back to his people he carried the bone with him. He had remembered the gully in which he killed his foe and had searched there until he found the bone although it had lain there over a half century. Just as Indian bones are still scattered over the country of the great west to this day, covered generally with earth but occasionally found exposed.

In 1865, Charles and Mitchell Sharp made a trip up the Elkhorn and located on land on the Humbug in what is now Stanton County. They did not remain there but came back to Omaha and on their way home met Jacob Hoffman and Frances Scott with their wives on their way back to the same locality with ox teams.

Hoffman and Scott were really the first white men to settle in that part of the state in what in later years was surveyed out as Stanton County. Stanton County is one of the smallest counties in the state and one of the most prosperous. It has an area of 432 square miles and contains 253,303 acres of land. The town of Stanton was started in 1870 and made the county seat which it is now.

| home |